|

In 2011, I had the pleasure of attending Lorimer Moseley's workshop, "Understanding Pain and Clinical Applications". My reason for re-posting this recap is because OTP recently released a 2-disc DVD set of his updated presentation. The objective of this two day workshop was to provide us with a scientifically based and clinically relevant, guiding framework for effective patient management. The three components of this framework were:

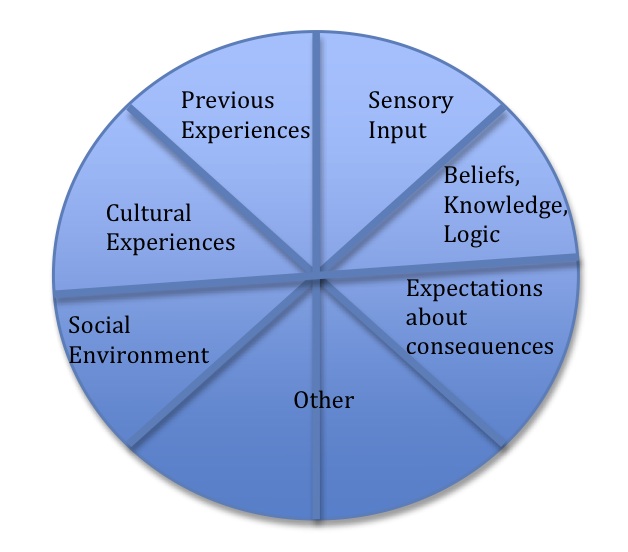

As always, I must first disclose that the following recap is based on my own interpretations of what was covered and may not be a direct reflection of what was taught. For those of you who work with individuals with pain, athletes or not, it is important to understand that "pain" in and of itself is a complex entity. Hopefully most of us are aware that its defiinition has long evolved past Descartes' "bottom-up model" and that this conscious experience is comprised of many systems designed to protect us from threat. The systems potentially involved include:

And as Lorimer suggests, pain can be conceptualized as a conscious correlate of implicit perception. "Pain relates to perceived danger" "Pain is a protective response that occurs in consciousness" Perception, meaning that our brain is continually evaluating actual or potential threats, based on many variables (such as sensory input, previous experiences, cultural factors, social/work environments, expectations about consquences, beliefs, knowledge and logic) to provide us with a not-always-accurate conclusion of possible danger. Lorimer stressed that pain is a conscious experience, manifested by the activation of specific and personalized, though modifiable, wired networks within our brain collectively known as neurotags. These tags, originally known as neurosignatures, exist in a snapshot in time, are precise and depend on inhibition to accurately map, in the brain, the representation of pain. In the presence of chronic pain, however, precision of mapping becomes lost via disinhibition. Essentially, the experience of pain does not necessarily change...but its contributors do. Simple definitions

"Pain doesn't exist until it hurts" Throughout the weekend, Lorimer directly and indirectly provided ample opportunity to hone our skills for "explaining pain". For those of you unaware, he co-wrote the must read, "Explain Pain" with David Butler "Pain is of the body...but of your head" To effectively manage those experiencing pain, he suggested that we take a three-pronged approach that includes the explanation of pain, sensory discrimination, and graded motor imagery. In fact, rather than a pain management framework, he suggests that we adopt a "pain recovery" program. "Pain is optional" Explain Pain This is a pretty straight forward, though far from simple, cognitive approach of engaging the patient, identifying and reconceptualizing the threats, using humor, and providing stories, metaphors and yarns to gradually re-expose the individual. We must essentially get under their radar to understand why pain does not equal their MRI results. "People often describe fear instead of pain" "We need to look beyond the tissues that hurt" To optimally create change we must:

Sensory Discrimination and Graded Motor Imagery The concept of a body matrix was introduced as were the clinical utility of "left /right judgements" and "imagined movements". Left / Right judgements are intended to recruit the pre-motor cortex by re-inhibiting the neurotags that are inhibited in painful experiences. Imagined movements, on the other hand, may actually activate pain neurotags as they recruit the primary motor cortex so these often need to follow L/R judgements. Essentially we must provide subthreshold inputs to elicit precise inhibition of subcomponents of pain neurotags. For more information, the NOI group provides an excellent clinical tool for use in clinic. Click here to access this resource. So, it is important to understand that graded motor imagery involves the recruitment of the premotor cortex in order to plasticize the non-painful neurotags in a staged/graded harmless manner. "Pain more associated with the nervous system becomes even less associated with the tissues" The Painful Athlete While treating the athlete was not a focus of this workshop, it is important for me to discuss the relevance of an effective management plan when working with athletes who experience pain especially since pain catastrophizing and fear avoidance are common in the training room. While exercise is perhaps the utmost priority in rehabiliation (see Putting Manual Therapy in Perspective), "training the brain" is probably the most effective way of doing so. In particular, motor control based rehab via targetting the central nervous system to induce "change"

We know that the brain is neuroelastic and since we do not want to perpetuate painful or faulty movement patterns, we must be specific with program design and implementation. Simply asking an athlete to "activate" a muscle just isn't enough. Further, cueing also plays a significant role in training the brain as Gabrielle Wulf's work tells is that we should strive to utilize external cues as much as possible. As for sensory discrimination, kinesiotaping techniques are an excellent tool to pull from your shed to provide continuous non-noxious stimuli and facilitate biofeedback and optimal motor patterning. One way of conceptualizing this is by considering that teenager who won't step away from their video game. Think of the video game as a pain neurotag. Playing for one hour is acute pain. Playing for hours on end is chronic pain. He can't stop playing. It won't stop hurting. So you buy him an iphone. Playing with the iphone is equivalent to the non-painful neurotag. He plays with the iphone for 5 minutes. 5 minutes becomes 10 minutes. 10 minutes becomes 20 minutes and so on. This n0n-painful stimulus (the iphone) is slowly and gradually distracting him away from his painful experience, the pain neurotag, the videogames. Eventually he outgrows the video games and there you have it! Finally, we can progress graded motor imagery to graded motor learning and control in many different ways but it is important that we respect the buffer zones that enable us to protect our athletes from crossing their tolerance boundaries. As both Lorimer and Dr. Stuart McGill suggest, it is always important to recognize and increase your athletes' capacities, but to do so in a graded and gradual manner. A special thank you goes out to Cynergy Education for hosting this workshop but even more gratitude goes to Dr. Moseley for his wonderful insight and expertise.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |