|

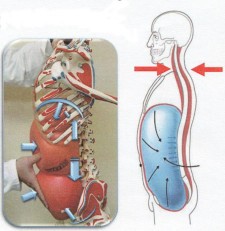

It's been over a year since I first began the Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization program. Since that initial "A" course, my clinical thought process has expanded exponentially through following up with the "B" and "C" courses, my privileged opportunity to visit Motol in Prague, and the day to day reflections of my current practice. Well recently, I had the privilege of taking part in another DNS A course that was put forth by Michael Maxwell of Somatic Senses and taught by Alena Kobesova and Brett Winchester. This particular experience was quite special for me because not only was it local (hence no flight costs), but it provided me with the opportunity to share my experiences to date with many of my friends and colleagues who attended the course...including my wife. I would say however, that the most beneficial aspect of being present was that it afforded me the opportunity to "fill in the gaps". Now while I would say that my current understanding of the DNS approach ("it's not a technique, it's an APPROACH") is quite solid, I do believe that like sport, it certainly will take years of deliberate practice to master. So let me share some of the knowledge shared throughout this most recent course that helped me fill in the gaps. Some of the information below will be based on the course material and others will be based on my thought processes as my mind traveled a million miles a minute. As always, please remember that these were my own interpretations. And for those of you who have yet to read my previous reviews, please make sure you click on the links above. Here we go... In general, there are two schools of thought to Musculoskeletal Medicine: Structure and Function. While we normally focus on structure, it is often forgotten that we really cannot have one without the other. And while in our later years (especially in today’s society) structure may certainly play a role in dictating function, in developmental kinesiology, it is known that function governs structure. Therefore, viewing MSK medicine in this light may provide us with a more accurate model of care. The unfortunate news however, is that unlike anatomy, functional norms have still yet to be clearly defined. If you look at bodybuilders, martial artists and runway models, which of the three would you say is the ideal? I know what you are thinking but is there a "why" to your answer? If you think about it, babies no nothing about bodybuilding, martial arts and modeling, they simply achieve “normal” posture on their own...using neurophysiology to change (aka develop) their own posture to explore the world. "It’s not just that the baby 'grow’s up'…it’s CNS development." Therefore, developmental patterns are related to the environment and are likely ideal. And this gives us every reason to study developmental kinesiology. Speaking of development, the arch of the foot forms around 4 years of age. So if a mother brings in her 3 year old child to your clinic because little Johnny has flat feet, just agree…and don’t put orthotics underneath the child’s feet! (Disclaimer, you do have every reason to evaluate for dysfunction however) Many of you are familiar with Stuart McGill's work. And many of you are likely aware that much of his research investigates loads on the spine. Like McGill, it was stressed within the course that it is often not external load that really hurts us, but internal load. That is, the load placed on our bodies through muscular contraction. Because lacking functional joint centration (maximal instantaneous congruency between two joint surfaces) decreases balanced activity between musculature, resulting in relative muscle hyperactivity. And it is this relative muscle hyperactivity that exceeds the body's physiological capacity resulting in potential injury (amongst other potential mechanisms of course). One example to conceptualize is the hamstring strain. Often the common explanation is a "weak glute". This may or may not be the case but consider decentration of the opposite foot sending a "chain-reaction" up the body, resulting in compensatory hyperactivity of supposedly stabilizing muscles. Therefore rendering (for example, the hamstring) a victim due to its new found force generation responsibilities. Because as the DNS folk would put it, a deficient punctum fixum results in greater activity of its associated muscles, likely leading to strain or tear due to compensation from contributing to the deficient punctum fixum. It's a ripple effect, if you will. Note: If you're "releasing" an acute hamstring strain you may be missing the boat. Speaking of which, “Are you treating the body’s compensations? Or on what’s wrong/the cause of dysfunction?” The moral of the story...if one segment is dysfunctional, it can compromise the whole system. Search for the key link! Another gap filler I took home with me was the importance of the sensory system. From tactile sensation to proprioception, optic, vestibular and acoustic, Janda taught that we must respect the bottom up approach of environmental feedback during clinical management. I previously wrote about the short foot but for those of you unaware, the inability to attain a short foot (what I call "dead feet") may increase the activity of larger muscles upstream and lead to injuries not dissimilar to the example I provided above. Another consideration is spinal stenosis. Early on in this short career of mine, such a presentation often led to guarded prognoses. However, as I've learned throughout the year utilizing a "DNS mindset", spinal stenosis may simply be thought of as a desperation by the body to utilize structural anatomy to stabilize the spine due to decreased stability and motor control of the core musculature. And spondylolistheses? Well, you can probably guess my answer. Think about it, the next time a patient presents with a spondylolytic spondylolysthesis, it may be wise to assess and determine whether or not a diastasis recti is present. You're likely to find one. Because rather than a 6 pack being the ideal, my thought process has shifted toward the "belly". And although it may look like some individuals solely possess a 6 pack, if you ask a successful powerlifter to load up under a bar with shirtless (ouch), you’ll probably see that he actually possesses a "belly". Several questions were asked throughout the weekend about releasing restrictions. "Shouldn't we release the muscle first if it's adhesed"? Some might argue "yes" but I've learned to counter with the question, of why is it restricted in the first place? Is it doing the job of something else? You also may remember the above image. If not, it's a diagram of the "stabilizing system of the spine" by Panjabi and depicts the important 3-way interaction between the nervous system, the musculature and the passive structures. Unfortunately, this 3-way interaction is often forgotten by many practitioners today. Because how often do we solely address the muscles and / or joints, yet forget the important contribution of the neural system? And as Alena asked, "How did his ’92 papers not change our treatment philosophy? Why are we still “fixated” on just joints and muscles?" So we must remember that understanding the functional standpoint of joint centration is respecting the role the CNS plays in control. For more information on this, make sure you take the time to read some of Peter Reeves' work. During the course Brett Winchester discussed the role of the anterior structures of the core which prompted me to post the following on facebook. "I think we can be even more precise with our thoughts on the rectus abdominis. We've moved away from flexion to anti-extension. But we can move even further away toward contribution to IAP. If we think about this muscle as a team player then maybe we'll be less confused." Because in my opinion, very often, the Rectus isn’t for flexion nor is it for anti-extension, it’s for IAP to buttress the spine against erector load. For those of you that work in the sport setting, yet still have a difficult time comprehending DNS principles, here is a little quote from a recent article about Steven Strasburg.

“To throw a baseball properly, a pitcher must get into the right position at the right time with the right succession of movements, like dominoes falling. Disruptions in this kinetic chain, as experts call it, cause problems at the weakest link, most often the elbow or shoulder.” Note: Clare Frank goes into more detail on the “whole body approach” in this interview, courtesy of pttalker.com. “Good diaphragmatic function is like a natural manipulation with every breath” So as you can see, DNS is about filling the gaps. It's amphoteric nature of every exercise being a test and every test being an exercise certainly widens my continuum of assessment and exercise, effectively deepening my toolshed. It's about facilitating breath where patients lack and engaging muscle activity where inhibited and/or decreased. And for those of you who have learned this approach, you will see why, from a clinical perspective, I believe that very few people need more open kinetic chain training in rehabilitation. We need to spend more time respecting centration and the body's support function just a little bit more. But most importantly, learning the DNS approach will get you into the habit of asking "why". And as a clinician this should be your primary question. Because in it's truest sense, "The definition of “Failed Back Syndrome” is operating on a consequence, not a cause"

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |