|

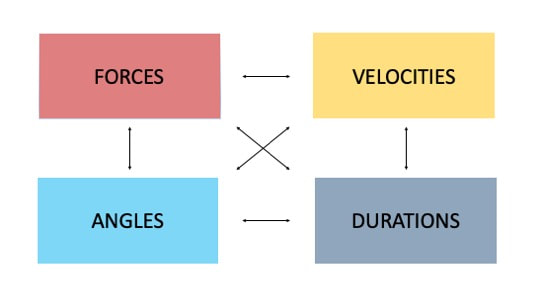

Here is a VERY brief summary of my notes taken from Coach Pfaff's short workshop on Dribbles during the ALTIS ACP I attended in early 2019. It should be noted that these notes are based on my understanding and interpretations so will defer to Dan and the ALTIS staff, as well as those more experienced for any corrections. However, I have included a video below from Coach Enyia that is both detailed and succinct. Dribbles: An upright, truncated drill that can be utilized at any point during rehabilitation and performance training for the purposes of improving stiffness, as well as promoting and stabilizing coordination of human locomotion. In addition to the sporting environment, dribbles can and have been used in gait retraining, neurorehab, and general musculoskeletal therapy. In the early phases of rehabilitation (for example with ankle injuries and hamstring strains) walking dribbles can be initiated. Dribbles regressed to this form may not only help preserve coordination but also assist in initiating soft tissue healing and regeneration through increased rate of circulation as well as controlled mechanotransduction. We know that the plantar venous pump is stimulated via muscular compression and contraction so any opportunity to do so actively should permit a more seamless return to pre-injury locomotion. Following this, progression can move toward jogging dribbles and eventually acceleration dribbles. The main constant in dribbles, regardless of speed, is a full heel to forefoot/toe rolling contact. Posture is upright and stable, yet exhibiting a dynamically controlled rhythm at all times. Depending on athlete need and ability, three different heights can be used, ankle dribbles, calf dribbles, and knee dribbles. Additionally, progressions would move from a more basic concentric (circular) shape to a more elliptical (egg) shape. Again, with respect to early stages of rehabilitation, one can maximize safety with concentric ankle dribbles. Finally, as tissue remodelling is influenced by forces, velocities, angles and duration, it is important to incorporate the various combinations of each . Loading must be varied and widespread as opposed to unidimensional and and linear. Progressions Mode:

Heights:

Shapes:

Loading Parameters:

0 Comments

What if? What if the answer keys to our educational exams were questions? With a few blank spaces for even better questions? What if, instead of “answers”, google searches turned up hits of even more questions? Searcher:

What if we had Q&Q periods instead of Q&A? What if Siri actually started asking us questions instead of the opposite? What if? - These questions tend to have an expansive effect. They allow us to think without limits. Curiosity is the foreplay of discovery. Discoveries are not the fruit of outstanding talent, but rather of common sense enhanced and strengthened by technical education and a habit of thinking about scientific problems. You can tell whether a man is clever by his answers. However, you can tall whether a man is wise by his questions. On average, we ask 40,000 questions between the ages 2 and 5 and steadily decline in our question-asking thereafter. Einstein said, The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing. One cannot help but be in awe when he contemplates the mysteries of eternity, of life, of the marvellous structure of reality. It is enough if one tries merely to comprehend a little of this mystery every day. Never lose a holy curiosity. What if we returned to asking more questions? Making seemingly random connections across disciplines... *Hyperlinks contained within. Please make sure you jump into these rabbit holes! Norman Doidge "But if it’s uncertain that our ideals are attainable, why do we bother reaching in the first place? Because if you don’t reach for them, it is certain you will never feel that your life has meaning. And perhaps because, as unfamiliar and strange as it sounds, in the deepest part of our psyche, we all want to be judged." The Gains of Drudgery A nice little piece from the Art of Manliness: "Suppose a man gives up his youth to the struggle for some coveted degree, some honour or award of the scholarly life. It is very possible that when he obtains that for which he has struggled, he may find that the joy of possession is not so great as the joy of the strife. It is part of the discipline of life that we should be educated by disillusion; we press onward to some shining summit, only to find that it is but a bastion thrown out by a greater mountain, which we did not see, and that the real summit lies far beyond us still... Thus though such a man may not gain the prize he sought, he has gained a command over his chance desires, a discipline of thought, a power of patient application, a steadiness of will and purpose, which will stand him in good stead throughout whatever toils his life may know in the hidden years which lie before it... So true is this, that Lessing, who was among the wisest of thinkers, said, that if he had to choose between the attainment of truth and the search for truth, he would prefer the latter. The true gain is always in the struggle, not the prize." The Currency of Likes Funny thought came to mind. In general, it is human nature to hold likes with high currency. This is hard to deny given the state of society we live in. However, when giving them out ourselves, they seem to hold low currency and value. We are very liberal and generous. What message are we sending? Maybe we should hold them a little closer? Anton Chekohv "Man will only become better when you can make him see what he is like." Emotion, Professionalism and Boundaries In many professions, strict - or should I say thick - boundaries are strongly recommended if not required. Doctor - Patient, Teacher - Student, Employer - Employee to name a few. These are important, without question, though often with transactional relationships as a side effect. Joe Ehrmann in "Inside Out Coaching" speaks of the importance of transformational over transactional relationships, yet discourses lacking emotion promote the latter rather than the former. Here's a piece from David Brooks on putting relationship quality at the center of education. Curiosity in Schools...Or a Lack Thereof More on schools... "Schools are missing what really matters about learning: The desire to learn in the first place." - Susan Engel The Laws of Human Nature by Robert Greene and 12 Rules for Life: An antidote to chaos by Jordan B. Peterson These two are my most recent reads. Here are some of the most vivid excerpts that stood out to me. The Laws of Human Nature

12 Rules for Life

Making seemingly random connections across disciplines... *Hyperlinks contained within. Please make sure you jump into these rabbit holes! The Present Some people choose to receive The Present when they are young. Others when they are in middle age. Some when they are very old. And, some people never do. Four Stages of the Creative Process - Graham Wallas

Preparation - The work that you put in. Your research, your reading, your writing, your thinking. Not unlike the overcoming of inertia. Attacking the problem from all angles. Incubation - The simmer. The stage of "unconscious processing." This can take two forms; active and passive. The first, active, is where other unrelated conscious tasks are performed. Working on one's car, arranging a jig-saw puzzle, tackling another project. The second, passive, is where one simply is taking a break. Going for a hike, walking the dog, swimming laps, etc. Illumination - The a-ha moment when the answer bursts into one's consciousness. In the shower. Mid-Sunday morning run. Often when we're least expecting it and with minimal, if any, exertion. Verification - A return to the conscious. The integration of the eureka back into your research, your reading, your writing, your thinking. Giftedness, inborn talents - Nietzsche "Do not talk about giftedness, inborn talents! One can name great men of all kinds who were very little gifted. They acquired greatness, became 'geniuses' (as we put it), through qualities the lack of which no one who knew what they were would boast of: they all possessed that seriousness of the efficient workman which first learns to construct the parts properly before it ventures to fashion a great whole; they allowed themselves time for it; because they took more pleasure in making the little, secondary things well than in the effect of a dazzling whole." - Nietzsche "Why don't we learn this in school?" In an age of information and opinion overload, learning foundational tenets is paramount. So is learning how to think critically. Harari states, "In a world deluged by irrelevant information, clarity is power." Our schooling is a stepping stone. To learn the necessities and to develop critical thinking skills. To learn what is relevant and to learn how to develop a filter. A filter that is important now, more than ever. See the forest. Foundational Skills Common to the Best Therapists - Stuart McMillan

From Stu's twitter feed. Includes some discussion on whether or not Compassion should be included either in place of, in addition to, or integrated with Empathy. My personal opinion is that compassion (I care) can make empathy (I understand) so much more powerful. On that note... Gospel of Relaxation (1899) - William James A small, but powerful excerpt from this classic essay by William James: “One of the most philosophical remarks I ever heard made was by an unlettered workman who was doing some repairs at my house many years ago. ‘There is very little difference between one man and another,’ he said, ‘when you go to the bottom of it. But what little there is, is very important.’" Appropriately, I'm reminded of the old adage, "Stop managing your time. Start managing your focus." Also, as it pertains to the modern day prevalence (recall, this was written over a century ago) of the culture of overwork or "grind", James further states: "Some of us are really tired (for I do not mean absolutely to deny that our climate has a tiring quality); but far more of us are not tired at all, or would not be tired at all unless we had got into a wretched trick of feeling tired, by following the prevalent habits of vocalization and expression. And if talking high and tired, and living excitedly and hurriedly, would only enable us to do more by the way, even while breaking us down in the end, it would be different. There would be some compensation, some excuse, for going on so. But the exact reverse is the case. It is your relaxed and easy worker, who is in no hurry, and quite thoughtless most of the while of consequences, who is your efficient worker; and tension and anxiety, and present and future, all mixed up together in our mind at once, are the surest drags upon steady progress and hindrances to our success." REST by Alex Soojung-Kim Pang

My most recent read and one of my three favorite books this year. Here are some teasers:

Making seemingly random connections across disciplines... *Hyperlinks contained within. Please make sure you jump into these rabbit holes! CURIOSITY Some considerations when in a teaching, guiding, mentoring, and/or motivational role. Inspired by “The Psychology of Curiosity” - G. Loewenstein Curiosity is the feeling of deprivation we experience when we identify and focus on a gap in our knowledge. The student needs to feel this gap. They must have some level of knowledge or awareness before they can get curious. In a way, they need to be beyond the “don’t know what they don’t know stage”. Therefore, often “to induce curiosity about a particular topic, it may be necessary to ‘prime the pump’”. To use intriguing - stimulating - teaser information to get them interested in order to actually become curious. TRUST Some words on trust, from Brene Brown: “Trust is the stacking of small moments over time, something that cannot be summoned with a command - there are either marbles in the jar or there are not. Trust is a living process that requires ongoing attention...You cannot establish trust in two days when you find yourself in a crisis; it’s either already there or it’s not.” This is an imperative consideration should a disconnect between two individuals be sensed. Even better, this should be considered proactively. Consistency in actions, always play the long game. ASK THEM Continuing from above, this excerpt is from Brett Bartholomew's Conscious Coaching Field Guide. "Quit trying to tell people everything you know. A more effective approach is to ask them about what they know. Learning about their world will help you modify your approach and provide more opportunities for you to reframe and relate a concept to help them better understand." CROSS-POLLINATION I believe the value of lateral thinking / cross-pollination of ideas is immense. When we think of an individual whom we consider wise, often it's because of their ability to link connections across disciplines. Steve Jobs states, "That's because they were able to connect experiences they've had and synthesize new things. And the reason they were able to do that was that they've had more experiences or they have thought more about their experiences than other people." Further, as Maria Popova states, “… in order for us to truly create and contribute to the world, we have to be able to connect countless dots, to cross-pollinate ideas from a wealth of disciplines, to combine and recombine these pieces and build new castles.” FAILURE A quick note on this, not unlike everything else. I recently failed an online exam. The one time exam required an 80% in order to pass and this was made clear prior to taking. Although I was aware of this, it was my choice to go ahead and take the exam - unprepared - during a short block of time in between patients. The exam took me 26 minutes to complete, of which a maximum time of 80 minutes was allotted. I achieved 75%. Although devastated, I was glad this happened. Really, my heart sank. But guilty as charged. As the saying goes, "Success is the worst teacher." Should I have passed the exam, I would have received my certificate and CE credits. But most importantly, I would have failed to obtain a deep understanding of the material. I have since gone back to immerse myself neck deep. As I tweeted recently, "If you're going too fast, life will somehow find a way to give you a speeding ticket. Heed its warning before you get into an "accident." This was my speeding ticket. SOCIAL Back in the blogging days it wasn’t uncommon to be called out on one's content in the comments section. This peer review or critical appraisal in my opinion was conducive to getting better. Other than twitter, I’m not sure this happens much anymore. Especially on instagram. Today, it's far too easy to block those who disagree with one's opinion and as a result little accountability exists. It's okay to not "like" a post. Again, "Success is the worst teacher." NEW VOCABULARY JOMO

TSUNDOKU

DARE TO LEAD

I just finished Brene Brown's newest book. Here are some of her one-liners to leave you with:

Here’s a glass of wine. 🍷 Let’s suppose we take this glass and drink it at 5pm. Fantastic. We then refill it and consume another glass at 5:30pm. Great. At 6pm we have another. And at 6:30pm another. Finally, at 7pm, within approximately two hours, we have our 5th glass. In general, how will most of us feel? Now let’s say we’re rehabbing from an injury or perhaps trying a new training program - marathon running, crossfit, yoga, whatever - for the first time ever. We have our first high intense session on Monday. We’re feeling great. We have a second session on Tuesday. Smooth. The same on Wednesday...if you recall, we’re either recovering/rehabbing from an injury or starting a novel training program. And again we train on Thursday. Not feeling so hot after all. Back to the wine. Let’s say we have our first glass at 5pm. The second glass we drink at 6:30pm. We enjoy those glasses, take a bit of a break, and have another at 9pm. Knowing that we’re not driving for the evening, we have a small glass at 11 or even call it quits at three glasses. In general, how will most of us feel? Often we are quick to point blame to specific muscles and joints when in fact a simple “too much too soon” is at play. Cumulative load within a short time period will often set us up for failure. Keep it simple.

​Just wanted to expand on this a little.

First, this exercise is not new. Recently it's been called the Copenhagen Adduction exercise while ten years ago it was called the Bunkie exercise for the Medial Stabilizing Line. Prior to that, I'm sure it's had its fair share of names as well. Many currently use it for adductor strengthening while others use it to isometrically load the MCL during early stages of rehab. Some use this exercise for torso control and others may even use it for the shoulder. In my opinion, it may be one of many valuable rudimentary exercises to include in a GPP circuit. What's most important though, is to use it appropriately. While the goal would be to use the longest possible moment arm for the longest reasonably possible duration, many in early stages of rehab are unable to do so. There simply is no way to hide it. So for very early stages of adductor or MCL strength loading, it's best to keep the moment arm as short as necessary and choose the appropriate starting point for duration. If starting with a ten second hold, each subsequent repetition would be one second less in duration. A countdown. 10, 9, 8, 7, 6....and so on. As one progresses, each subsequent repetition can then be performed with a slightly longer moment arm, where the line of force moves distally. Again, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6...and so on. From here we have several options. Once the individual is able to load for strength distally, it would be appropriate to load for endurance. Therefore, starting distally, if the athlete is able to load for five seconds (for example), then they may be able to perform 5 x 5 sec holds while shortening the moment arm with each subsequent repetition. From here, it is possible to progress with a longer duration first repetition (i.e. 6, 5, 5, 5, 5) as well as a minimizing the amount of moment arm shortening so that the line of force stays as distal as appropriately possible. The possibilities are endless. This is not to make things more complex, it is to make the exercise more appropriate. It's simple progressions and regressions with the goal of progressive adaptation. Years ago I wrote about exercises for plantar sided foot pain. Much of what I thought back, then I still think today. However, there are two key principles I overlooked that currently find very important. That is,

For the former, many are aware of the importance of extension of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. It is not uncommon to see many ways of improving mobility of said joint. What I have learned over the years however, is that attacking first MTP mobility is futile in the absence of medial arch mobility. That is, in order for the first metatarsal to clear room for the phalanx to extend, the joints upstream must be in doing their job well. It's not uncommon to see arthopathy and spur formation at the junction between the cuneiform and first metatarsal, so before we aggressively stretch and mobilize the first MTP joint, we need to ensure that we give respect to all joints of the foot and ankle. One isn't more important than the rest. As for the latter, it was noted by Thomas Michaud that collectively we often strengthen the foot in neutral and/or plantar flexion. And that we often fail to do so in toe extension, if not eccentrically in toe extension. Concentric toe flexion exercises are common. So are eccentric toe extension exercises. What aren't so common are isometric and eccentric exercises, in closed kinetic chain, and in toe extension. These are key in athletics/sport and they are paramount in fall prevention in the elderly. In the video below are some progressions of low level foot strengthening exercises. For the complete videos, simply go to my youtube page. And for those curious, I'm using Toe Spreaders from The Foot Collective. There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you I stopped writing several years ago. It wasn't a big deal, it just wasn't there. The waters stood still so to speak. Looking back, there came a point in time where I had nothing to say. Not that I did before - touché - but I didn't enjoy writing if I felt like I needed to post for the sake of posting.

Today, we exist - I wish I could say "live" - in an era where posts are forced. Social media used to be a destination, today it exists as an avenue. Be it Instagram, Facebook, whatever. I would say blogs as well but in this circle of life, it's easier now to short post on IG than it is to write a blog. Not too long ago, blogs evolved from diary and journal entries to opinion pieces to "scientific" regurgitations. There was a lot of cut and paste. No shortage of references, simply a shortage of thought. To each their own. But for me, the ink ran dry. I learned a lot over the last decade. I learned how to chase. And I learned first hand the effects of "the chase." It was a decade of accumulation. One where in the first half of the decade my thoughts and opinions were shared along the way. In the second half, all I had were thoughts. It got to me. Some use the phrase #alwayslearning. Again to each their own. I prefer sometimes learning. And sometimes living. Sometimes thinking. And sometimes reflecting. Sometimes relaxing. And sometimes writing. I guess. I think we can learn a lot from each other. Especially when we openly share our thoughts and opinions. But I think we need to be more honest with ourselves and actually have thoughts and opinions of our own. We need not be afraid to be wrong. More often than not we're almost right. But be ourselves we must. If the above is indicative of anything, it is this: My mind is spinning, bordering on gibberish. And the urge to write is there. Maybe it's to organize my thoughts. Possibly to solidify my opinions. Regardless, it is there. For me. I knew this day would come. If the goal is to develop the shoulder and arm's contribution to pulling, doing so with the scapula relatively fixed appears to generate the most force production and minimal GH joint wear.

In this video, I performed Prone Kettlebell Rows (isometric holds) and progressed in bell size until form significantly diminished.

A focus on "pinching the shoulder blades" - or retracting the scapula - would have disallowed the load I was able to achieve. This would be very clear to those who perform loaded rowing movements on a regular basis. As mentioned above, a fixed scapula appears to generate the most force production.

Whether dragging sleds, playing tug of war, or helping someone from falling off a cliff, most likely do not focus on pinching the shoulder blades. Particularly with heavy loads, the shoulder girdle generally assumes a centrated position and holds itself there with an isometric contraction enabling the remaining segments of the upper extremity to function in phasic contraction. Including the lower extremities (thinking dragging sleds). This is why yielding isometric holds are being utilized above. This message should not be confused with never retract or even never retract with pulling.

This brings us to Bat Wings. Dan John states that the aim with his exercise should be indeed to squeeze the shoulder blades together. Often as hard as possible. Those who are familiar will admit the ease of which loads heavier than the exercise intends may be used. Thus, my preference is the use of the FRC principle of End Range Lift-offs and perform Bat Wings in such position.

The aim here is short-range neurological control and force production. Or, increasing the surface area under the left side of the arc of the length-tension relationship curve. A reminder that requisite mobility precedes. Meaning, adequacy with no external load prior to the use of external load. Elevating the kettlebell/dumbbell - a minimum of 7 inches off the floor facilitates proper Lift-off starting position, but more importantly, prevents the use of heavier loads than would be effective. Bracing and maximal irradiation are a necessity here.

At the end of the day, however, the system - a set of things interconnected - will "produce its own pattern of behaviour over time." (See @drmchivers for more information on Systems Thinking.) And the above, are ways of training its component parts.

|